We all know that bad data in = bad data out.

When contract data is unstructured, everything downstream suffers.Manual billing and invoices, messy spreadsheets, and hours of reconciliation that never quite tie out.

Tabs fixes that.

We’re the AI-native revenue platform that automates the entire contract-to-cash cycle. Whether you're selling custom terms, usage-based pricing, or a mix of PLG and sales-led, Tabs turns month-end chaos into clean cash flow.

✅ Instantly generates invoices and revenue schedules from complex contracts✅ Automates dunning, revenue recognition, and cash application✅ Syncs clean, structured data across your ERP and reporting stack

Trusted by companies like Cortex, Statsig, and Cursor, Tabs powers the finance teams behind the next wave of category leaders.

Most execs brag about how much they raised.

Bill Zerella bragged about how little he needed.

Fitbit scaled during an era of VC excess — not by spending more, but by thinking smarter. While competitors raised hundreds of millions (literally), Fitbit reached $1B+ in revenue on just $22 million of outside capital.

That’s not just capital efficiency. It’s operational clarity at its finest.

And for PE-backed operators with timelines, hurdle rates, and real accountability, it's a case study in turning financial discipline into enterprise value.

Constraint Built the Mindset

Fitbit didn’t have a VC-fueled war chest. They were shipping physical devices — with long lead times, complex logistics, and unforgiving margin profiles.

You don’t blitzscale hardware. You survive it like a marathoner with a half-full tank.

“Especially for hardware businesses, it's really critical… if you're growing really rapidly and you're not attentive, you can easily get buried with an enormous liquidity issue if you're not careful.”

— Bill Zerella, former CFO of Fitbit

That constraint created a mindset: every dollar must return — quickly.

Retail Was the Cash Engine

Most see retail as a margin drag. Zerella saw it as a float engine.

Here’s how:

A customer buys a Fitbit at Best Buy

Fitbit collects cash in 30 days

Fitbit pays the manufacturer in 60–90 days

Each sale funded the next — no outside capital required.

“Retail was actually our cash engine.” — Bill Zerella

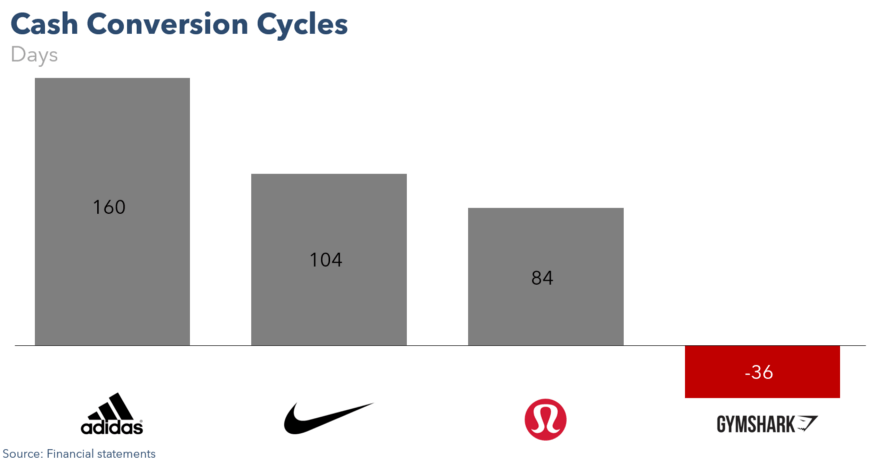

Same pattern shows up in D2C. Take Gymshark:

“Gymshark negotiated terms so good they were paying suppliers after selling to customers... You’re actually paying with the customer’s money. That’s the dream.”

— Taylor Holiday, CEO of D2C Marketing Agency “Common Thread”

TL;DR: Float = Freedom

When customers pay you before you pay your suppliers, you unlock negative cash conversion cycles (CCC) — a massive advantage in capital-scarce environments.

Gymshark had 36 days of cash on hand per unit sold

They used that to finance growth — no external capital needed

Meanwhile, long A/R cycles are effectively interest-free loans to your customers

Float isn’t just financial hygiene — it’s a business model advantage.

Capital Discipline in Practice

Where others chased momentum, Fitbit chased math. Everything — GTM expansion, hiring, inventory — had to justify itself through working capital math.

“If you overbuild, then you're going to have a bunch of inventory that you got to pay for that hasn't been sold yet, and that's an enormous strain on working capital.”

— Bill Zerella

Their roadmap was built off earned capacity — not ambition.

They kept it tight with working capital facilities and supplier agreements. No interest, no warrants. Just leverage without dilution.

“We raised debt instead of equity to fund inventory — using cheaper capital for working capital.”

— Kingsley Afemikhe, CFO of Shield AI

This only works if you can forecast accurately and negotiate well. Suppliers weren’t just vendors — they were strategic partners.

“Your suppliers are partners in the dance of your survival.”

— Kingsley Afemikhe

Hiring Lagged Revenue — On Purpose

At Fitbit, new headcount had to be funded by existing margin. Not projected margin. Not “next quarter’s” margin. Real, in-the-bank margin.

“Many people die of indigestion more than they do of starvation.”

— Taylor Holiday

While most startups led with hiring, Fitbit followed performance.

A Playbook Built for the PE Era

Fitbit’s rise wasn’t a fluke of timing or category creation. It was a masterclass in operational leverage:

Turning working capital into a growth engine

Building supplier relationships that fund, not drain

Letting margins dictate growth pace

Keeping headcount lean and cash-backed

“Our efficiency was our moat.” — Bill Zerella

This was during a time when capital was cheap and everyone else was burning cash. That’s what makes it impressive — and relevant now.

Can You Build a Fitbit in SaaS?

You may not sell hardware — but you have a cash cycle:

A customer contract

A payment term

A gap between revenue and cost

Are you leveraging it?

Ask yourself:

Is your margin structure funding scale — or chasing it?

Could your vendors be financing your growth?

Would your hiring plan hold up if you had no new cash?

This is especially true with multi-year deals. If you're collecting annual payments upfront, that’s float — use it to fund product development, retention, and expansion before spending equity dollars.

You’re not just modeling ROI. You’re realizing it.